The journey of recovering from aneurysm repair represents a significant chapter in many patients' lives, touching not only on the mechanics of surgical intervention but also on understanding the broader condition itself. Aortic aneurysms present a unique challenge in cardiovascular health, often requiring careful management and timely treatment to prevent potentially life-threatening complications. This guide explores the nature of these vascular bulges, the factors that lead to their development, the warning signs that demand attention, and the comprehensive approaches to treatment and recovery that modern medicine offers.

Understanding aortic aneurysms: what they are and why they matter

Defining an Aortic Aneurysm and Its Impact on Blood Vessels

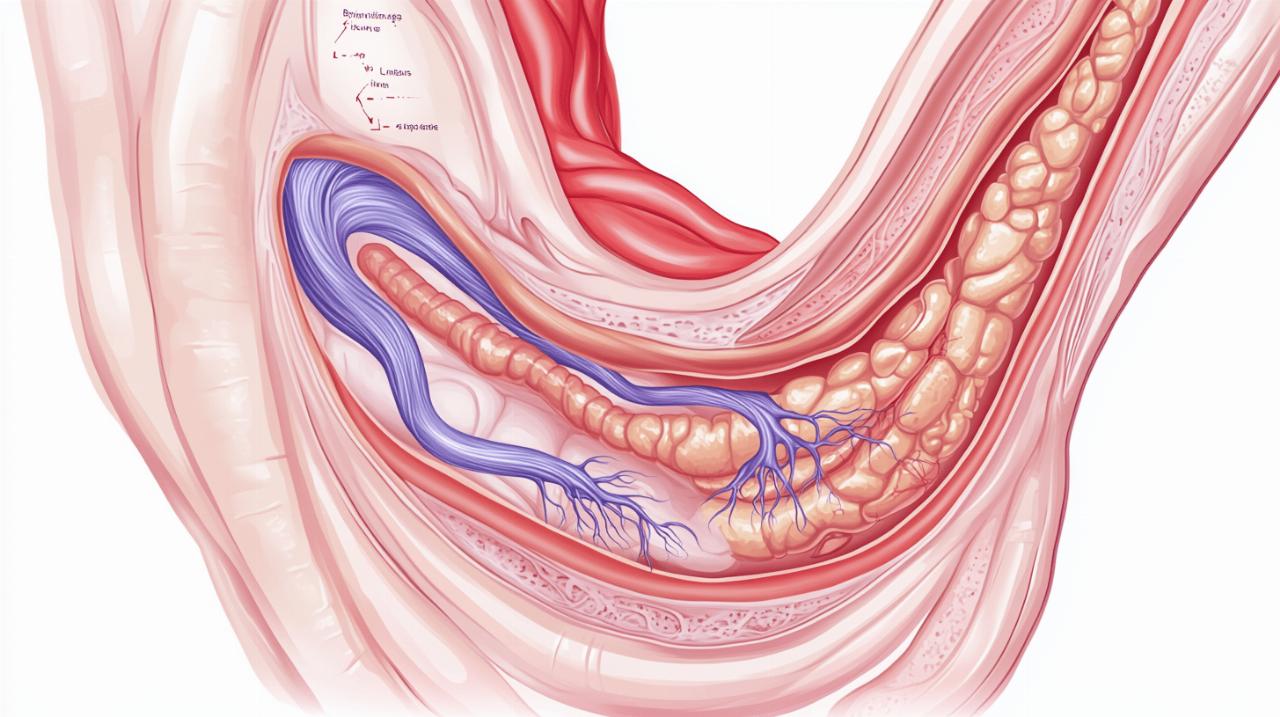

An aortic aneurysm occurs when a section of the aorta develops a bulge or swelling, resembling a weak spot in a tyre that balloons outwards. This bulging happens because the wall of the artery becomes weakened over time, losing the structural integrity necessary to withstand the constant pressure of blood flow. The aneurysm itself is not merely a cosmetic issue within the body; it represents a genuine threat to the vessel's stability. As the wall stretches and thins, the risk of rupture increases dramatically, potentially leading to catastrophic internal bleeding. The condition can develop in different regions of the aorta, including the chest area, known as a thoracic aneurysm, or within the abdomen, referred to as an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Both locations pose serious risks, though the mechanisms and symptoms may differ slightly depending on where the aneurysm forms.

The Critical Role of the Aorta in Your Circulatory System

The aorta serves as the main highway for blood leaving the heart, distributing oxygenated blood to every part of the body through an extensive network of smaller arteries. This vital artery runs from the heart through the chest and down into the abdomen, branching off to supply organs, muscles, and tissues with the nutrients and oxygen they need to function. Any compromise to the integrity of this vessel can have widespread consequences, affecting everything from kidney function to spinal cord health. Given the aorta's central role in maintaining circulation, even a small disruption can escalate quickly, making the detection and management of aortic aneurysms a matter of considerable clinical importance.

Root causes and risk factors behind aortic aneurysm development

How Hypertension and Arterial Disease Weaken the Aortic Wall

Hypertension, commonly known as high blood pressure, stands as one of the most significant contributors to the weakening of the aortic wall. Over time, sustained elevated pressure exerts continuous force against the inner lining of the artery, gradually eroding its strength and resilience. This relentless strain can cause microscopic tears and structural damage that accumulate, ultimately predisposing the vessel to dilation. Arterial disease, particularly atherosclerosis, compounds this problem by causing the arteries to harden and narrow. As fatty deposits build up within the vessel walls, they reduce elasticity and compromise the aorta's ability to respond to fluctuations in blood pressure. This combination of increased pressure and reduced flexibility creates an environment where aneurysms are more likely to develop, emphasising the importance of managing blood pressure and cholesterol levels throughout life.

Genetic Predisposition, Age, and Lifestyle Contributors to Aneurysm Formation

Beyond the mechanical stresses of hypertension and arterial disease, genetics plays a notable role in determining an individual's susceptibility to aortic aneurysms. A family history of aneurysms can indicate inherited weaknesses in the structural proteins of the artery walls, making certain individuals more vulnerable from birth. Age is another unavoidable factor, as the natural ageing process leads to a gradual loss of elasticity in blood vessels. Older patients are therefore more commonly affected by aortic aneurysms, reflecting the cumulative impact of decades of wear and tear on the cardiovascular system. Lifestyle choices, particularly smoking, significantly accelerate this deterioration. Smoking not only damages the lining of blood vessels but also contributes to the development of atherosclerosis and hypertension, creating a perfect storm for aneurysm formation. Other factors, such as certain genetic conditions that weaken connective tissue and, in rare cases, physical trauma to the aorta, can also contribute to the development of these dangerous bulges.

Recognising Warning Signs: Symptoms of Thoracic and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Early detection challenges and common symptom patterns

One of the most insidious aspects of aortic aneurysms is their tendency to remain silent for extended periods, especially when they are small. Many patients discover they have an aneurysm only during routine health checks or imaging tests conducted for unrelated reasons. This lack of symptoms makes early detection particularly challenging, underscoring the value of regular medical examinations for those at higher risk. As an aneurysm enlarges, however, it may begin to press against neighbouring structures, producing a range of symptoms that vary depending on its location. A thoracic aneurysm, situated in the chest, might cause pain in the chest or back, and can lead to coughing, hoarseness, or shortness of breath if it compresses the airways or vocal cords. In contrast, an abdominal aortic aneurysm often manifests as a deep, constant pain in the abdomen or side, sometimes accompanied by a noticeable pulsating sensation in the belly. These symptoms, though not always alarming on their own, warrant prompt medical evaluation to rule out the presence of a growing aneurysm.

One of the most insidious aspects of aortic aneurysms is their tendency to remain silent for extended periods, especially when they are small. Many patients discover they have an aneurysm only during routine health checks or imaging tests conducted for unrelated reasons. This lack of symptoms makes early detection particularly challenging, underscoring the value of regular medical examinations for those at higher risk. As an aneurysm enlarges, however, it may begin to press against neighbouring structures, producing a range of symptoms that vary depending on its location. A thoracic aneurysm, situated in the chest, might cause pain in the chest or back, and can lead to coughing, hoarseness, or shortness of breath if it compresses the airways or vocal cords. In contrast, an abdominal aortic aneurysm often manifests as a deep, constant pain in the abdomen or side, sometimes accompanied by a noticeable pulsating sensation in the belly. These symptoms, though not always alarming on their own, warrant prompt medical evaluation to rule out the presence of a growing aneurysm.

Emergency signs of aortic aneurysm rupture requiring immediate medical attention

The rupture of an aortic aneurysm represents a life-threatening emergency that demands immediate intervention. When an aneurysm bursts, the sudden release of blood into the surrounding tissues can cause catastrophic internal bleeding, leading to a precipitous drop in blood pressure and loss of consciousness. Patients experiencing a rupture typically report sudden, severe pain that is markedly more intense than any discomfort they may have felt previously. Dizziness, fainting, and signs of shock often follow in rapid succession. Recognising these emergency signs and seeking urgent medical care can make the difference between survival and death, as emergency surgery is required to control the bleeding and repair the damaged vessel. The survival rate following emergency surgery for a ruptured aneurysm ranges from 50 to 70 per cent, highlighting both the seriousness of the condition and the critical importance of early detection and elective treatment before rupture occurs.

Treatment approaches and recovery journey after aneurysm repair

Comparing Surgical and Endovascular Repair Options for Patients

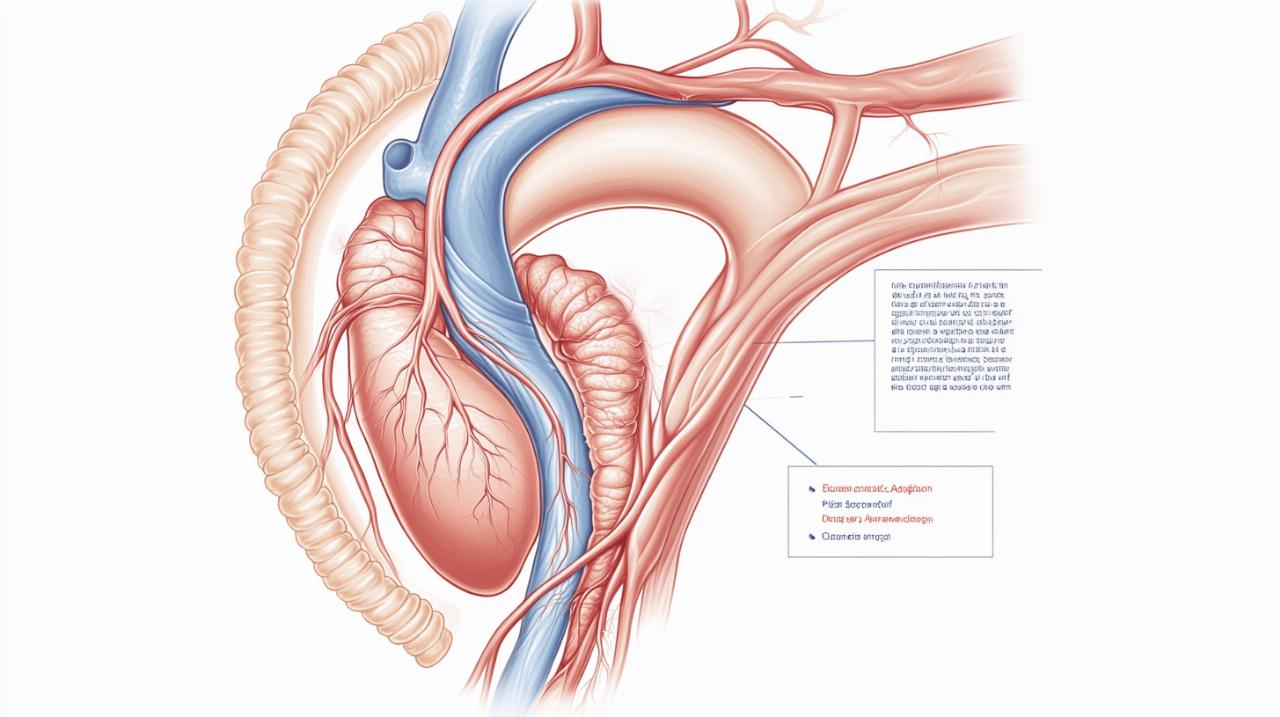

The decision regarding how to treat an aortic aneurysm depends on several factors, including the size and location of the aneurysm, its rate of growth, and the overall health of the patient. For smaller aneurysms that pose a lower immediate risk, doctors may recommend a period of watchful waiting, during which regular scans monitor the aneurysm's size and stability. Lifestyle modifications, such as stopping smoking, adopting a heart-healthy diet, managing hypertension, and controlling cholesterol levels, play a crucial role in slowing the growth of the aneurysm and reducing the risk of rupture. When an aneurysm reaches at least 5 centimetres in diameter, grows more than 1 centimetre per year, or shows other signs of instability, surgical intervention typically becomes necessary. Two main surgical approaches are available: open surgical repair and endovascular aneurysm repair, commonly known as EVAR. Open surgical repair involves making a large incision to access the aorta directly, removing the weakened section, and replacing it with a synthetic graft made of polyester. This traditional method, though more invasive, remains essential for larger or more complex aneurysms and offers the advantage of being a definitive solution when less invasive options are not suitable. The operation typically takes between 3 and 4 hours, with patients spending 3 to 10 days in hospital and requiring 4 to 6 weeks for full recovery. In contrast, endovascular aneurysm repair offers a less invasive alternative, particularly for abdominal aneurysms. During EVAR, a stent graft is inserted into the aorta via a catheter, usually through a small incision in the groin. The stent graft, a fabric tube supported by a metal frame, reinforces the weakened artery wall from the inside, effectively sealing off the aneurysm and restoring normal blood flow. This approach generally results in shorter hospital stays and quicker recovery times compared to open surgery, making it an attractive option for many patients. However, both procedures carry inherent risks, including bleeding, blood clots, infection, heart attack, kidney failure, and stroke. Specific complications such as endoleak, where blood continues to leak around the stent graft, or spinal cord injury leading to paralysis, though rare, must be carefully considered when planning treatment.

Post-Treatment Monitoring and Long-Term Management Strategies for Optimal Recovery

Following aneurysm repair, whether through open surgery or endovascular methods, the recovery process requires patience and careful adherence to medical advice. Patients can expect certain restrictions in the weeks following surgery, such as avoiding driving for 1 to 2 weeks and refraining from heavy lifting, defined as anything over 10 pounds, for 4 to 6 weeks. Proper care of the surgical incision is essential to prevent infection and promote healing. Beyond the immediate postoperative period, long-term management focuses on lifestyle changes and regular monitoring to ensure the success of the repair and to prevent further cardiovascular complications. A heart-healthy diet low in saturated fats and rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains supports overall cardiovascular health and helps control cholesterol levels. Medicines such as statins may be prescribed to further manage cholesterol, with guidance available through therapeutic lifestyle change programmes. Blood pressure management remains a cornerstone of post-treatment care, often involving medications such as beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers to keep hypertension under control. For those at risk of cardiovascular events, aspirin may be recommended, though it does carry an increased risk of bleeding. Quitting smoking is perhaps the single most important step a patient can take to improve outcomes, as smoking cessation dramatically reduces the risk of further aneurysm development and other cardiovascular complications. Physical activity, tailored to individual capabilities and approved by a healthcare provider, supports recovery and overall fitness, while stress management techniques help control blood pressure, particularly important for those with thoracic aneurysms. Patients are advised to avoid heavy lifting and stimulants such as cocaine, which can dangerously elevate blood pressure. Regular follow-up appointments and imaging studies remain essential to monitor the graft and detect any complications early. For patients who undergo elective surgery before rupture, the survival rate is impressively high, ranging from 95 to 98 per cent, underscoring the value of timely intervention. Living with a history of aortic aneurysm requires ongoing vigilance, but with proper management and a commitment to a healthy lifestyle, many patients go on to enjoy long, fulfilling lives. Working closely with a healthcare team, attending all scheduled check-ups, and maintaining open communication about any new symptoms or concerns form the foundation of successful long-term management.